In this post, we shall start talking about another great physicist whose contribution to the atomic theory is unparalleled – Niels Bohr.

Niels Bohr was born in Copenhagen on 7th October 1885. His father, a professor of physiology, ignited his interest in physics. In 1911, Niels Bohr spent 6 months with Sir J.J. Thompson in the Cavendish Lab. Later in 1912, he spent 3 months working under Ernest Rutherford in Manchester where he proposed a quantitative model supporting Rutherford’s structure of the atom. His model was called the the Bohr model.

Niels Bohr, a theoretical physicist, developed postulates to explain his atomic model, focusing on one-electron systems in the gas phase. This involved atoms with only one electron, such as H, He+, Li2+, etc., where the number of protons in the nucleus is irrelevant as long as the system has only a single electron revolving around the nucleus (e.g., Li2+ has three protons but only one electron).

Postulates of the Bohr model

When he developed his model, Niels Bohr, made certain assumptions based on the scientific data available at that time. These assumptions were called as the ‘Postulates’ of his theory. The postulates were as follows –

1] Electrons move in fixed orbits and the energy of the electron depends on the size of the orbit.

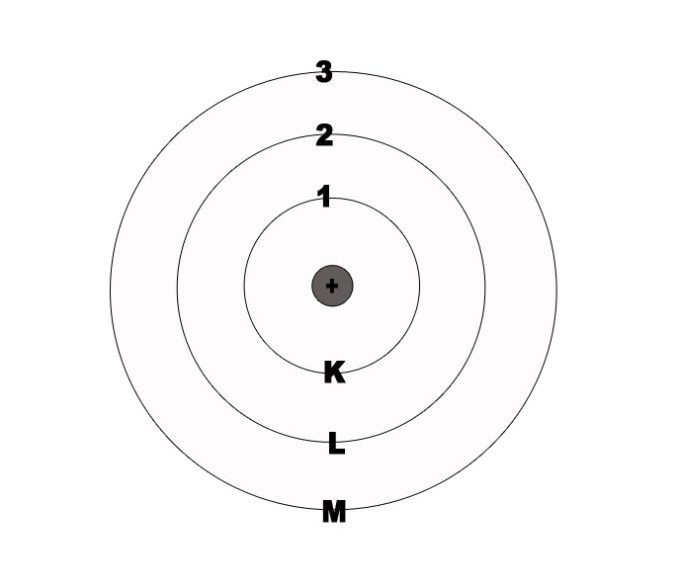

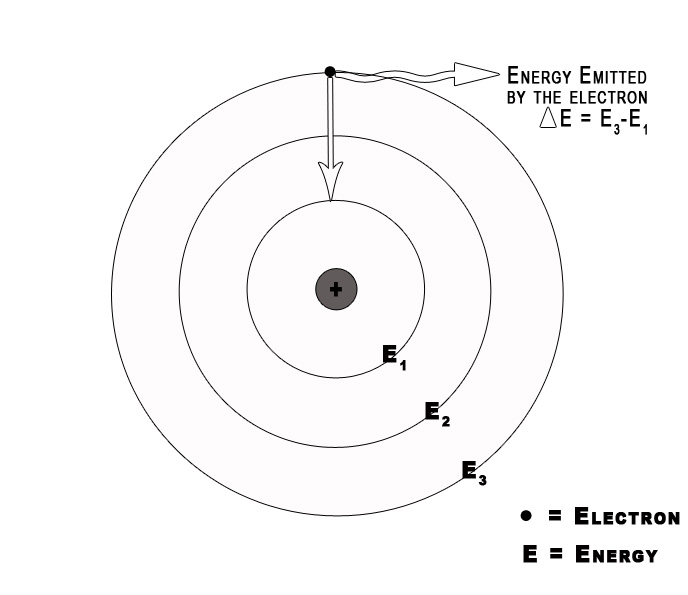

Niels Bohr corroborated Ernest Rutherford’s model of the atom. He proposed that the protons occupy the centrally situated nucleus and the electrons revolve around it in fixed, concentric circular orbits. Every orbit is associated with a certain amount of energy. These are called energy levels. The energy levels were denoted by numbers 1,2,3,4 .. or K, L, M, N.

2] The energy levels are quantised.

Bohr took Planck’s theory and used it to describe the structure of the atom.

Planck’s quantum theory –

1.Different atoms and molecules can emit or absorb energy in discrete quantities only. The smallest amount of energy that can be emitted or absorbed in the form of electromagnetic radiation is known as a quanta.

2. The energy of the radiation absorbed or emitted is directly proportional to the frequency of the radiation.

The energy of radiation is expressed in terms of frequency as,

𝐸 = ℎ𝜈

where,

𝐸 is the energy of tradition; ℎ is the Planck’s constant (6.626×10−34 𝐽.𝑠); 𝜈 is the frequency of radiation.

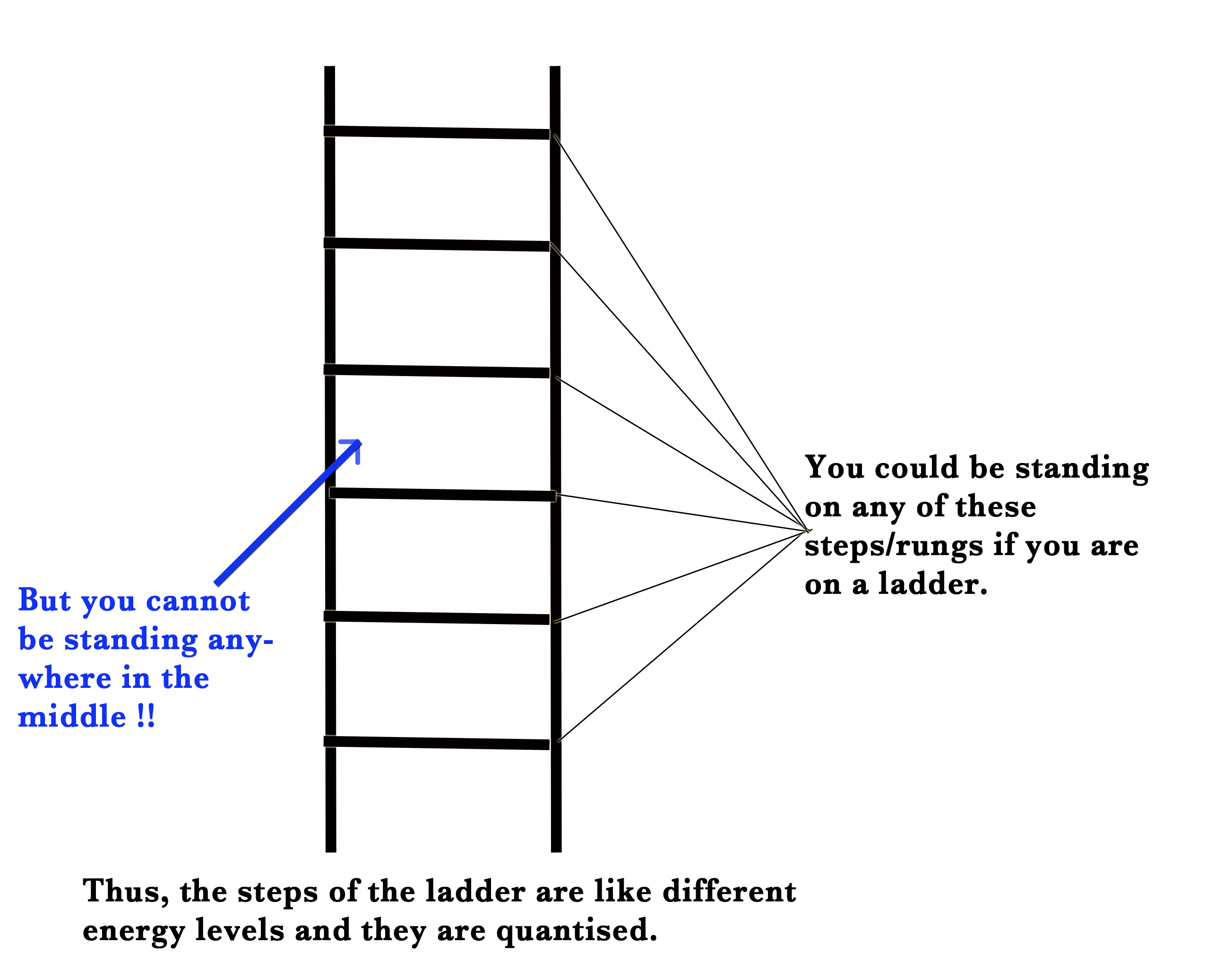

Similarly, Niels Bohr proposed that electrons occupy certain discrete orbits. The orbits are at specific distance from the nucleus and have specific energies. Thus, the energy levels in an atom are quantised i.e they can only take certain discrete values of energy. The electron can occupy only these specific energy levels and cannot appear anywhere between these levels.

To understand quantization, we could think of a ladder.

According to his theory, the atom has stationary orbits and their energy is quantised. The electrons can occupy only certain specific orbits which satisfy the quantum condition.

THE QUANTUM CONDITION

Niels Bohr assumed a quantum condition while deriving energy levels for the hydrogen atom. This quantum condition was not derived logically but somehow it explained the energy levels in the hydrogen atom well. Thus, physicists had no choice but to accept the assumption.

Niels Bohr suggested that the energy of an electron in any orbit is quantised through its angular momentum. The quantum condition put forth by him –

Electrons can occupy only those orbits, whose angular momentum (L) is an integral multiple of the quantity h/2π.

L = mvr = n (h/2π)

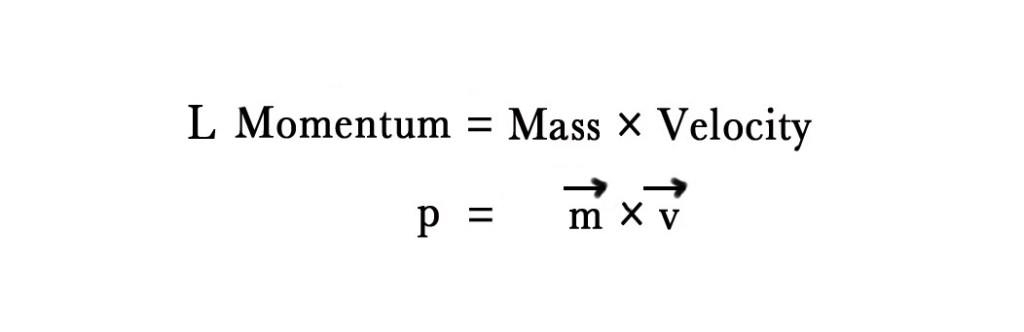

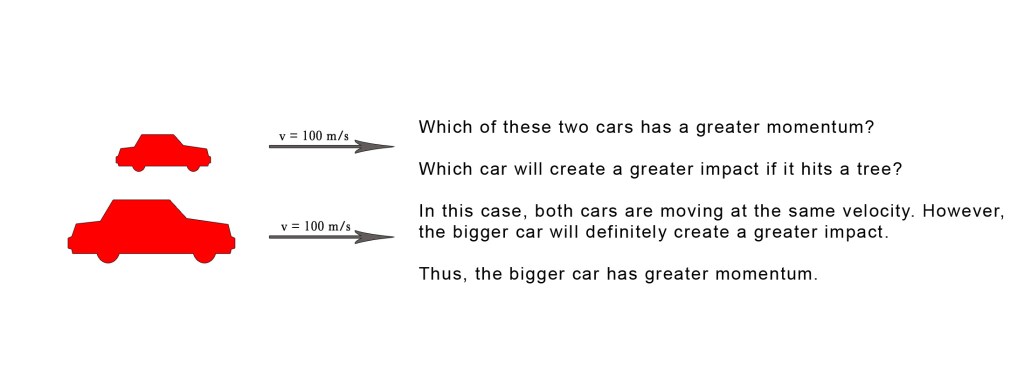

To understand this condition we first need to know the concept of momentum. In simple words, momentum can be described as the force or speed of an object in motion. Momentum is of two types –

1. Linear Momentum – Momentum of objects travelling in straight lines.

2. Angular Momentum – Momentum of rotating objects.

First let us try to internalise the concept of linear momentum.

In the above formula, the arrows on ‘m’ and ‘v’ indicate that they are vector quantities i.e. they have magnitude and direction.

When we talk about the speed of a car we are not specifying in which direction the car is moving. However, when we talk about velocity of that car both the speed and direction have to be specified. Thus, velocity is a vector quantity.

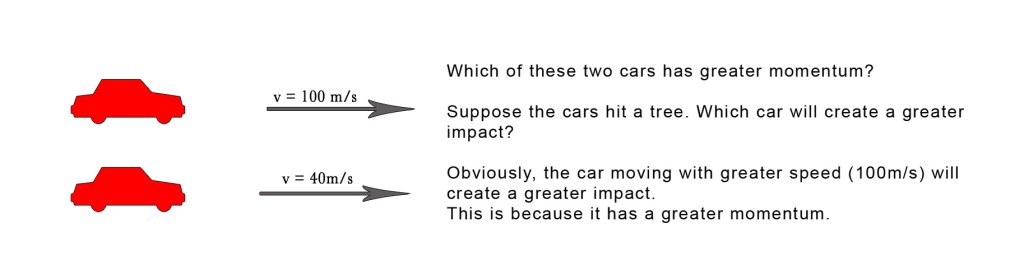

Consider the following example –

Now consider this –

The above examples show that the momentum is dependent both on velocity and mass of the object. Note that the cars are moving in a straight line and thus we are discussing linear momentum here.

The angular momentum applies to objects moving in circular paths – revolving/rotating objects.

e.g.- Planets moving around the sun, electrons moving around the nucleus etc.

The formula for angular momentum can be derived in two ways –

Thus, the angular momentum of an electron revolving around the nucleus (L) = mvr.

where,

m = mass of the electron

v = velocity of the revolving electron

n= integer (integral multiple) and n=1,2,3….etc.

h= Planck’s constant = 6.626 × 10-34 Js

π = 3.14 (constant)

Coming back to the quantum condition,

mvr = n (h/2π).

The right hand side of this equation has 3 constants namely – h, 2 and π. The value of is h/2π is 1.055 × 10-34 m2 kg / s.

Thus, the angular momentum of an electron can have only certain discrete values.

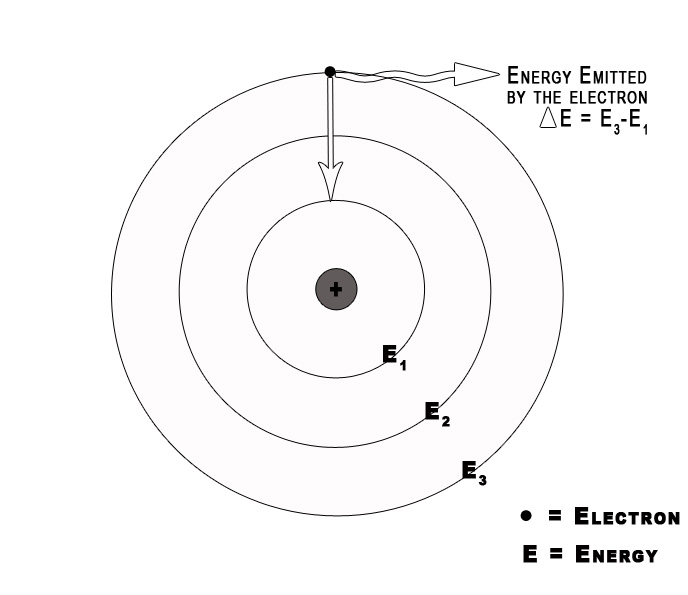

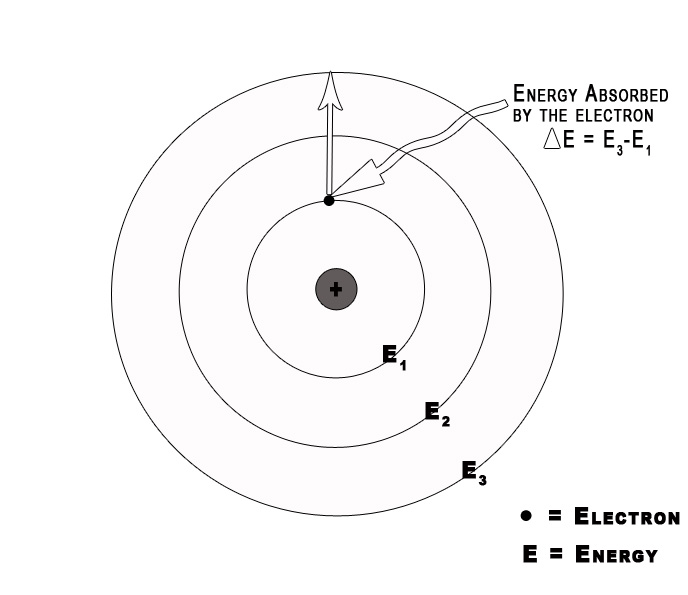

3] Electromagnetic radiation occurs only when an electron moves from one orbit to another.

As long as an electron stays in a given orbit it does not radiate energy. This indicates that the energy of an electron remains constant in a particular orbit. The energy of an electron changes only when it goes from a high energy level to a low energy level or vice versa.

4] Classical electromagnetic (EM) theory is NOT applicable to the orbiting electrons.

5] Newtonian mechanics is applicable to orbiting electrons.

6] Energy of the orbiting electron, Eelectron = Ekinetic + Epotential

Only the energy of the electron is considered for most scientific studies. This is because it is the electron that moves and not the nucleus. The nucleus is stationary. In Rutherford’s language –

“When we have flees on an elephant, it’s the flees that do all the jumping”

7] Planck – Einstein relation applies to electronic transitions –

ΔE = Efinal – Einitial= hν = hc / λ

ν ( pronounced as neu) = frequency = c/λ [NOTE ⇒ v = velocity and ν is frequency]

c = velocity of light

λ = wavelength (length between successive crests or troughs of a wave).

8] The distance of the electron from the nucleus is maintained due to force balance –

There are two forces acting on an electron moving in an orbit-

1. the centrifugal force (mv2/r) – This is a fictitious/ pseudo force i.e. it is NOT REAL. This force acts in the outward direction. It tends to push an object away from the centre of a circular path.

and

2. the centripetal electrostatic force (q1 q2 / 4π∈0r 2) – The nucleus is positively charged and the electron has a negative charge on it. Thus, there is an electrostatic attraction between them. This electrostatic force is the centripetal force acting inwardly.

According to the Bohr’s theory, these two forces balance each other. Thus, the nuclear collapse is avoided. This provided an explanation for the drawback in Rutherford’s atomic model.

Using the above postulates he derived his atomic Model. The derivation is interesting as it explains Bohr’s postulate in a better light. The derivation is as follows –

- Consider, an atom in one electron system and in gas phase, as shown in the adjacent figure.vThe nucleus has a charge Ƶ+ (Ƶ is the atomic number of the element in consideration)

Suppose we consider,

He+ then Ƶ= 2

Li2+then Ƶ= 3.

- Total nuclear charge = Atomic number × elementary charge.

q1 = (No.of protons) × (Charge on a single proton).

q1 = Ƶ × e … (1)

Similarly,

Charge on the electron = – (Charge on a single electron)

As the electron is negatively charged, the sign is negative and as this is a one-electron system, we consider only the charge on that electron.

q2 = -e ….(2)

- According to postulate no 5 , Newtonian Mechanics applies to the electron.

∴ The energy of the orbiting electron, Eelectron = Ekinetic + Epotential.

Ekinetic = (1/2)mv2 ⇒ Energy on account of the motion of the electron. The kinetic energy unit here is Joules (mass unit is kg and velocity is m/s2). This is a mechanical unit.

Epotential = (q1 q2) / 4π∈0r ⇒ Energy stored in the atom with opposite charges q1 q2. In this formula the unit of the charges, q1 q2 is Coulomb. This is an electrostatic unit. So, to convert the overall unit of potential energy to Joules (mechanical unit) we introduce a factor 4π∈0r. This factor thus helps us to put the electrostatic energy on the same plane as the mechanical energies. Now the units for both kinetic and potential energy are the same and thus we can simply add them to find the energy of the electron.

(The above formulas used for kinetic and potential energies are the standard formulas for the respective energies).

∴ Eelectron = [(1/2)mv2 ]+[(q1 q2) / 4π∈0r ].

=[(1/2)mv2 ] + [(Ƶe)(-e) / 4π∈0r ]… substituting for q1 q2 … from (1) and (2)

=[(1/2)mv2 ]-[(Ƶe2/ 4π∈0r ].

∴ Eelectron = [(1/2)mv2 ]-[(Ƶe2/ 4π∈0r ]…………. ①

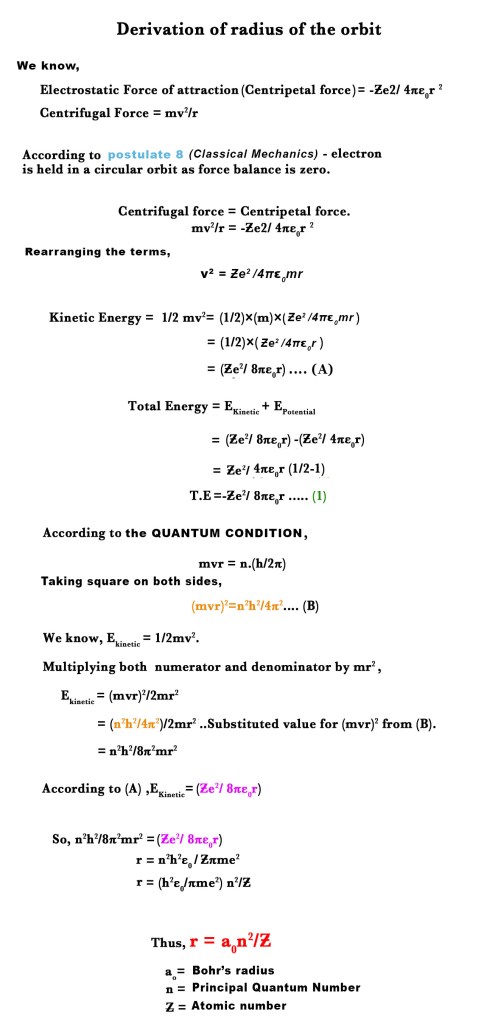

According to postulate no 8, the centripetal and centrifugal forces acting on the electron revolving in an orbit balance each other, thus keeping the electron from moving from its orbit.

Centrifugal force = mv2/r

Centripetal force = Electrostatic force = electrostatic or potential energy / distance ( As energy = Force × Distance, ∴Force = Energy/Distance)

Thus, The centripetal force = Potential energy / radius = (q1 q2 / 4π∈0r) × 1/ r = q1 q2 / 4π∈0r 2

∑ Force =FCentrifugal + Fcentripetal = 0

= Fdynamic + Felectrostatic = 0

= mv2/r +q1 q2 / 4π∈0r 2 = 0

∴mv2/r = – (q1 q2 / 4π∈0r 2 ).

∴mv2/r = – ( Ƶe2/ 4π∈0r 2 )… [ as q1 q2 = Ƶe2.] ………②

- And according to postulate no 3 ,

L = mvr = n (h/2π), n = 1,2,3.. ……③

When we solve for equations ①,② and ③, we get three important parameters –

1.Radius of the orbit

2. Energy of the electron in a particular orbit.

3. Velocity of the electron in the given orbit.

Radius of the orbit (r)

Let us derive the equation for radius of the orbit. For doing so, we first need to find out the kinetic energy for the system. Then we find the total energy by adding the kinetic and potential energies. Later we apply the quantum condition and use the Bohr theory postulates to derive an equation for the radius. The derivation goes as follows –

From the above derivation, we know that –

r = (h2∈0/4πme2) × (n2 / Z)

= (Constant)× (n2 / Z).

Since, h = 6.62 x 10-27 erg.sec

π = 3.142

m = 9.109 x 10-28gm

e = 4.803 x 10-10esu

∴ r = 0.529 × (n2 / Ƶ)

n= 1,2,3...

Thus, the radius of the orbit takes multiple values. They are quantised and non-linear (as the radius is proportional to the square of n).

e.g. H – atom , Ƶ= 1 and n= 1 (ground state) then r1 = 0.529 Å ≈ 1/2 Å – THIS IS THE BOHR RADIUS(a0).

Also, r α n2.

Radius is directly proportional to the square of the orbit number. This indicates that as we go farther away from the nucleus, the radius of the orbits increases.

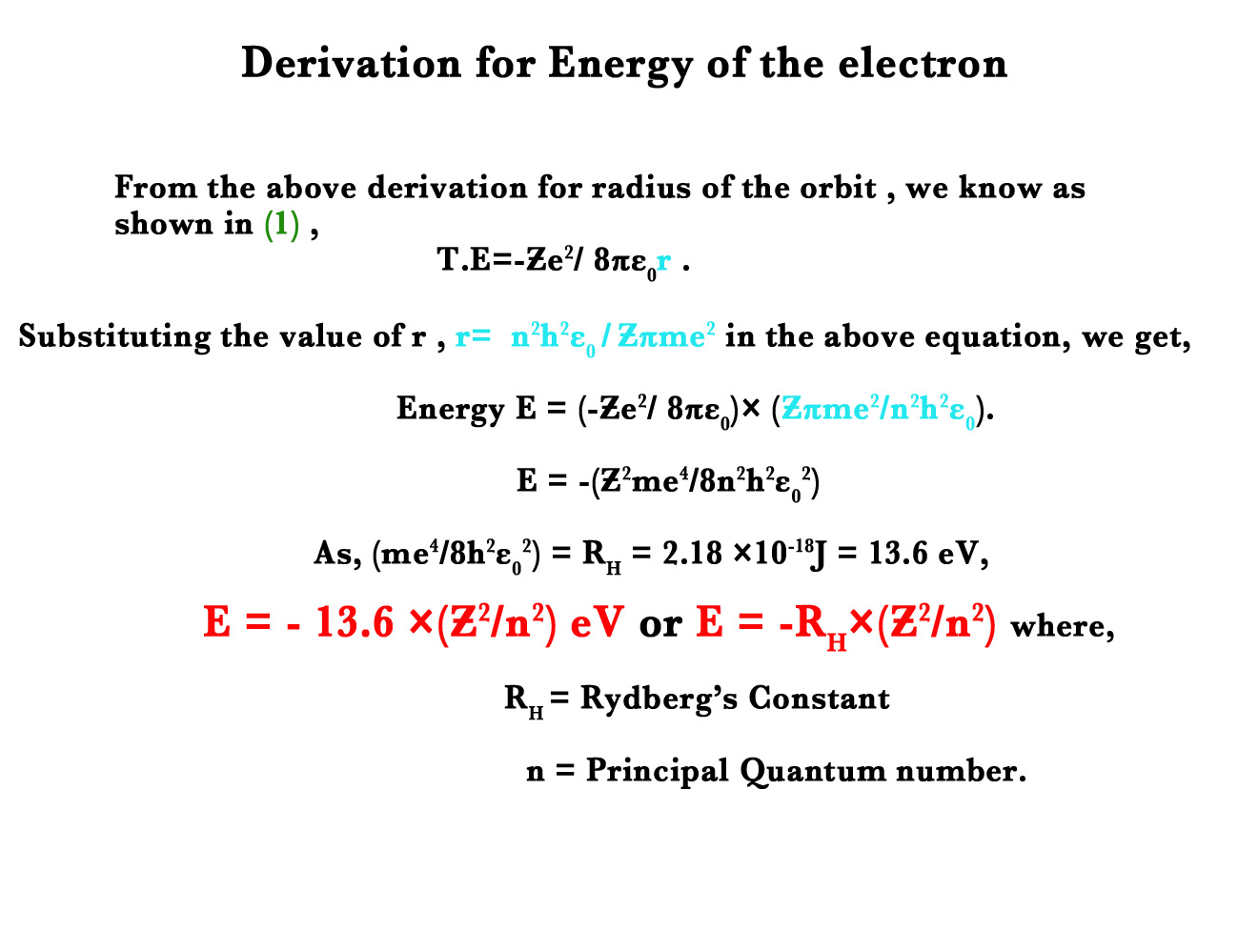

Energy of the electron in the given orbit (E)

Energy of the electron, E = – (me4/ 8∈0 2h2) (Ƶ2/ n2)

It is universally know that the Rydberg constant ,RH = me4/ 8∈0 2h2.

Thus, E= RH .(Ƶ2/ n2).

E(n) α (1/ n2).

Radius is inversely proportional to the square of orbit number. This indicates that as we go farther away from the nucleus, the energy of the orbits decreases.

The above equation confirms that energy is quantised too.

Electronic energy is always negative.

According to the Bohr’s atomic model, the maximum energy value of the electron at an infinite distance from the nucleus is zero. This is because there is negligible attraction between the electron and the nucleus at infinite distance. As the electron comes closer to the nucleus (as n decreases), the energy of the electron is lost and it becomes negative. The magnitude of the energy increases , however the negative sign remains constant. This negative sign means that the energy of the electron in the atom is lower than the energy of a free electron at rest. As the electron comes closer to the nucleus, it looses more energy. The loss of energy stabilizes the system.

3. Velocity of an electron (v) –

Learning the derivations is not compulsory. However, we must know the formulae for energy and radius of the orbits.These are important because they lead us to the understanding of other phenomena. The discussion on the Bohr model will continue in the next post too. Till then,

Be a perpetual student of life and keep learning…

Good Day!

References and Further Reading –

1)http://chemistry.tutorvista.com/inorganic-chemistry/bohr-s-model-of-the-atom.html

2)http://guide.ceit.metu.edu.tr/thinkquest/apndx3.htm