In the last post, we saw how quantum numbers were introduced to understand the structure of the atom. These quantum numbers describe all the necessary details about an electron in a given orbit. Let us start by understanding what these quantum numbers exactly tell us.

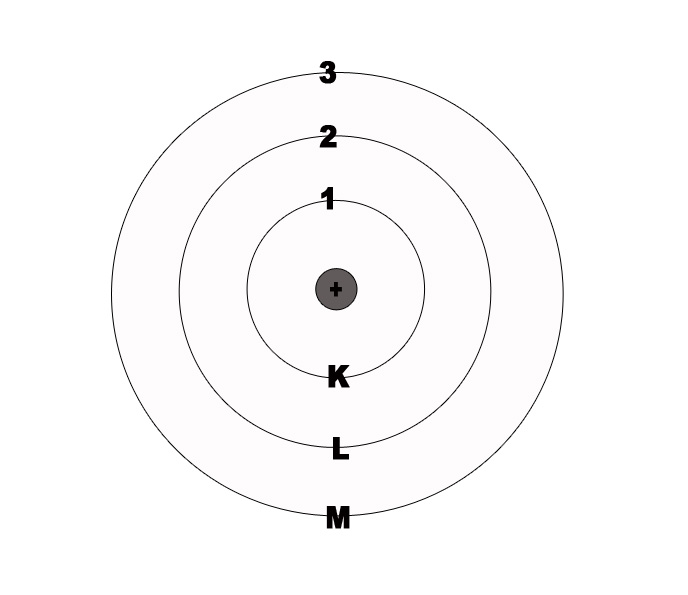

Principal Quantum Number (n)

This parameter divulges information about the size of the orbit, its distance from the nucleus, and the orbital energy.

e.g.- If n=1, then it indicates that we are looking at the orbit which is closest to the nucleus i.e the ‘K’ shell.

n=2 indicates the second orbit from the nucleus i.e. ‘L’ shell. This orbit is farther from the nucleus as compared to the ‘K’ Shell.

The maximum number of electrons allowed in any principal shell is given by 2n2.

For the first shell (K), n=1. The allowed no of electrons is 2(1)2 = 2.

For the second shell (L), n= 2. The allowed no of electrons is 2(2)2 = 8.

For the third shell(M), n= 3. The allowed no of electrons is 2(3)2 = 18.

For the fourth shell(N), n= 4. The allowed no of electrons is 2(4)2= 32.

Azimuthal or Orbital Quantum Number (ℓ)

According to the Bohr-Sommerfeld atomic model, the electrons only travel in certain orbits of specific energy. This was termed quantisation. The model proposed that the orbits have different shapes. The azimuthal quantum number was used to denote the shape or angular distribution of the orbital. This quantum number can take values from 0 to n-1. It increases in steps of unity, where n is the principal quantum number.

ℓ = 0 indicates a s-orbital, which is spherical in shape. This gives sharp lines in the spectra.

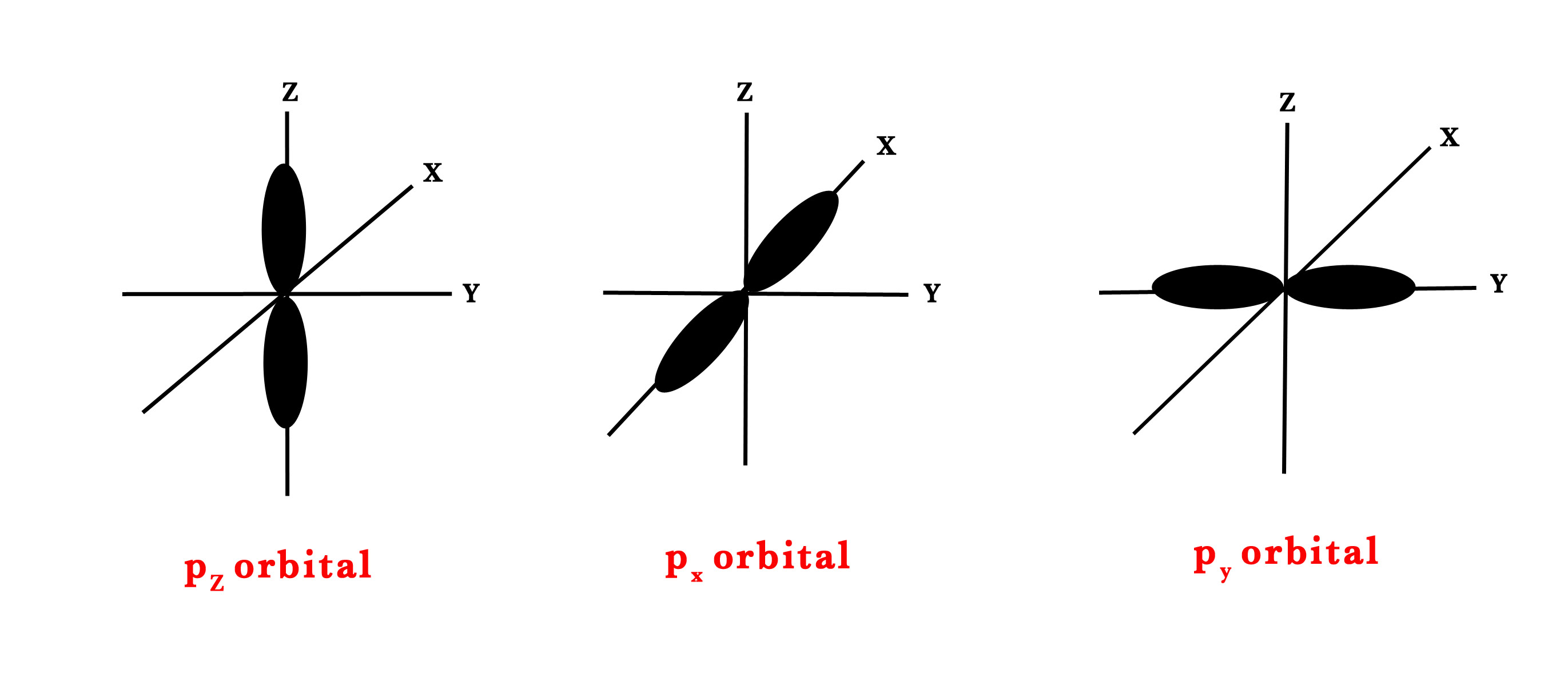

ℓ = 1, indicates a p – orbital, which is elliptical/elongated.

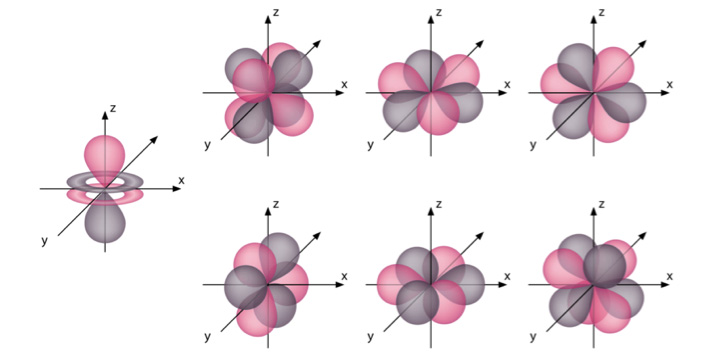

ℓ =2, indicates a d- orbital, which has a complex shape.

ℓ = 3, indicates an f – orbital, which also has a complex shape.

The spectroscopic notations for these are

s⇒ sharp lines

p⇒ principle lines

d⇒ diffuse lines

f⇒ fine/fundamental lines.

These are just characterizations of the kind of lines that were observed by the Spectroscopists for each orbital. Thus, the names s, p, d, f.

Magnetic Quantum Number (m)

Another concept that improved the Bohr model was that the orbitals don’t have to lie in the same plane. The orbitals are oriented in different directions in space. The orientation of the orbitals in space is described by the magnetic quantum number. This quantum number tells us how the orbitals look in 3- dimensions and how they are oriented in space. This quantum number can take values from –ℓ to +ℓ.

m = –ℓ..0..+ℓ.

The s-orbital is spherical, ℓ = 0,m=0. This means that the s-orbital is evenly distributed in space i.e. it’s spherical.

But for p-orbital, ℓ=1. So, m= -1,0,+1. Thus, there are three types of orientations in space for the p-orbital (shown in the figure below). It could be on the x, y or z-axis. Thus, we have px, py, and pz orbitals.

m= -1 ↔ py.

m= 0 ↔ pz.

m= +1 ↔ px.

When ℓ=1, m = -2,-1,0,1,2, representing the five d-orbitals dxy, dyz, dxz, dx2-y2, dz2.

The structure of the seven f-orbitals,namely , 4fy3 – 3x2y, 4fxyz , 4f5yz2 – yr2 ,4f5yz2 – yr2,4f5xz2 – xr2,4fzx2 – zy2,4fx3 – 3xy2,is more complex and can be represented diagrammatically as follows –

The electrons occupy the f-orbitals only after the element Cerium (Atomic weight = 58). These f-orbitals are under the valence shell and rarely play an important role during reactions. Thus, they are not studied in detail at a preliminary level.

Spin Quantum Number (s)

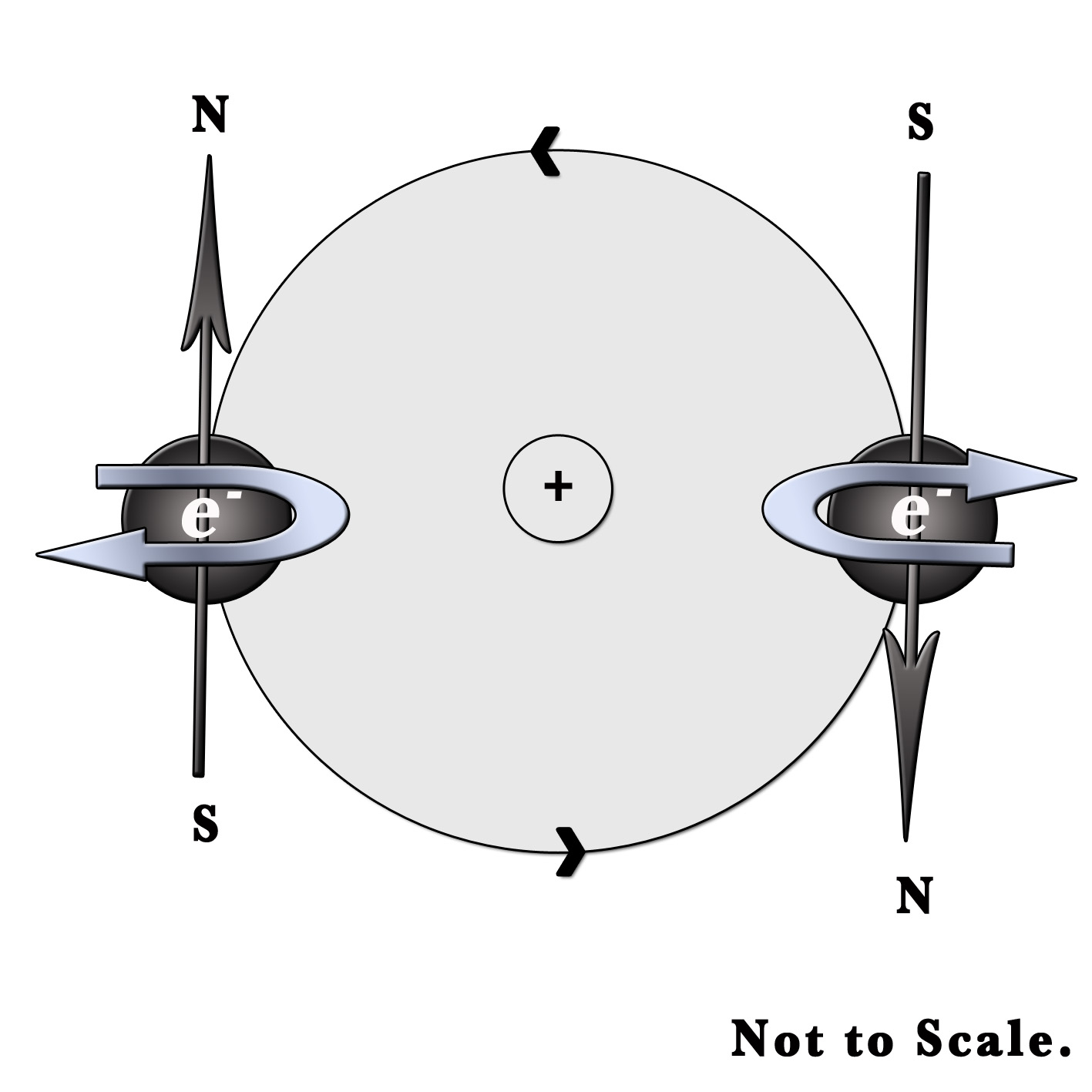

This quantum number explains the magnetic properties of substances. Just like our earth, the electron not only revolves around the nucleus but also spins around itself. It can spin in the clockwise or anti-clockwise direction. A moving charge generates a magnetic field. The direction of this field can be found out by the right-hand rule. Imagine holding a rod in your hand. Four fingers are wrapped around the rod and the thumb finger is stretched along its length. According to this rule, the 4 fingers of the hand represent the direction of motion of the electrons. The stretched thumb represents the direction of the magnetic field produced. Only two orientations are possible for electrons as they can move clockwise or counterclockwise.

In the above figure, one electron is spinning clockwise and the other is moving anti-clockwise. Thus, the two electrons have opposite magnetic orientations with different spins. One has a North pole (N) and the other has a South pole (S) of the induced magnetic field. These two spins cancel each other out. Yet, in the case of an unpaired electron, the spin generates a magnetic field. This gives rise to several magnetic properties.

Thus, for each value of magnetic quantum number(m), the spin quantum number (s), has two values – s= +1/2 and s=-1/2.

Thus, the 4 sets of quantum numbers help describe the structure of an atom.

|

Principal Quantum Number |

Azimuthal/Orbital Quantum number |

Magnetic Quantum Number |

Spin Quantum Number | |

| Symbols |

n |

ℓ |

m |

s |

| Spectroscopic notations |

K,L,M,N.. |

s,p,d,f |

– |

– |

| What does it tell us? | Size of the orbit, Distance from nucleus & Orbital energy | The shape of the orbital, no. of sub-shells present in the principal orbit/shell. | Orientations of the sub-shells(X, Y, Z-axis). | The direction of electron spin i.e Clockwise or Anti-clockwise. |

| Why is it required? | To explain the main spectral lines. | To explain the splitting and the hyperfine structure of spectral lines | To explain the splitting of lines in a magnetic field. | To explain the magnetic properties of substances. |

The naming of the orbitals is done as follows-

n | ℓ | m | Orbital Name | Allowed no of electrons = no.of orbitals ✖️2 |

n = 1 | ℓ=0 (s-orbital) | 0 | 1s | 2 |

n = 2 | ℓ = 0 (s-orbital) ℓ = 1 (p-orbital) | 0 -1,0,+1 | 2s 2px, 2py, 2pz | 8 |

n = 3 | ℓ = 0 (s-orbital) ℓ = 1 (p-orbital) ℓ = 2 (d-orbital) | 0 -1,0,+1. -2,-1,0,+1,+2. | 3s 3px, 3py, 3pz 3dxy,3dyz,3dxz, 3dx2-y2,3dz2 | 18 |

We shall learn how these quantum numbers were useful in studying the elements in our next post. Till then,

Be a perpetual student of life and keep learning…

Good day!

Note – The tables above may not be seen properly on your mobile screen. You may need to scroll a bit. It is advisable to view this post on an iPad or laptop screen.

References and Further reading –

- Lecture 5, MIT open courseware 3.091 by professor Donald Sadoway.

- http://antoine.frostburg.edu/chem/senese/101/electrons/faq/f-orbital-shapes.shtml

- http://www.tulane.edu/~sanelson/eens211/crystal_chemistry.htm

- Precise Chemistry textbook by Sheth Prakashan Kendra.

Image source –

1) http://www.tulane.edu/~sanelson/eens211/crystal_chemistry.htm